Image from shutterstock

“Reputation, reputation, reputation! Oh, I have lost my reputation! I have lost the immortal part of myself, and what remains is bestial.” – Cassio, in Shakespeare’s Othello.

Thankfully for Sydney’s lawyers, Cassio is not the only person who’s ever been worried about their reputation being trashed. In our last blog post, we talked a bit about what defamation is, how the courts determine whether something constitutes defamation, and how the rise of social media has increased many ordinary people’s potential liability when it comes to being accused of defamation. The new prominence of social media isn’t the only change to the defamation law landscape that’s arisen in the online era, though…

Jurisdictions, jurisdictions, jurisdictions.

One of the biggest legal headaches for anyone involved in a defamation action is the matter of jurisdictions.

What do we mean? Well, maybe you’ve read a crime novel where the following kind of situation occurs: A man is shot while hang-gliding in California. The glider keeps going, and he dies while over North Dakota, eventually coming to a rest in, say, Hawaii. Now you have three groups of cops all claiming that the crime occurred in their “jurisdiction”, plus the FBI, as they point out that they’re responsible for aviation matters.

This scenario probably doesn’t occur very often in real life when it comes to murder cases, but it’s practically par for the course in defamation. What happens when someone in New Zealand writes a potentially defamatory article, which is hosted on a Japanese website, about someone living in England? Where was the article “published”?

That’s hard to say. In Australia at least, we have a little more clarity on the matter. An important High Court decision from 2002, Gutnick v Dow Jones, decided that a Victorian man (Gutnick) could sue for defamation over an article posted to an American website, since it was accessed/downloaded in Australia and caused damage to Gutnick’s reputation here.

That’s good news if you find yourself in Gutnick’s position, although no guarantee that you’ll ever see a dollar from a successful action. If someone overseas is accusing you of defamation, you’re on safer ground, but the matter of jurisdictions in online defamation is to a great extent unsettled law in most countries. We’d highly recommend that you check whether their court case was successful if you ever decide to go for a holiday to that country.

What should you do if you believe you have been defamed online?

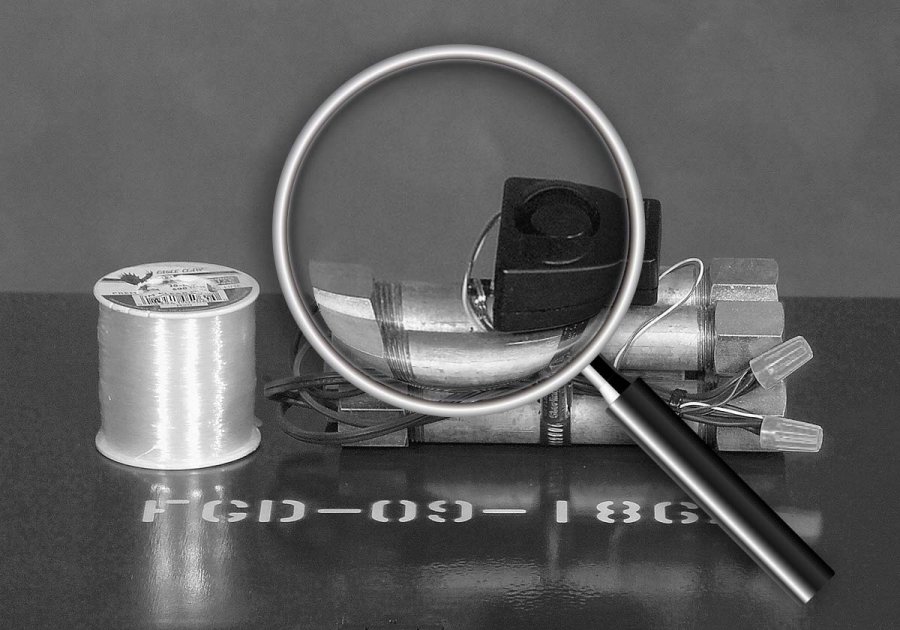

Well, probably the first thing you should do, if the matter is serious enough, is call a lawyer. Private eyes like us may have plenty of opinions to give you, but ultimately we’re not qualified to dispense legal advice.

However, a private investigation firm with a properly resourced computer forensics department can be mighty handy to have on your side if you open your web browser one day to be greeted with a bunch of slander. One problem with the internet can be the issue of (apparent) anonymity. If someone decides to tell the world that you break into people’s houses at night and steal their cats, they might not do it with their real name next to a photo of them smiling and giving a double thumbs-up. Instead, they could choose to set up a Twitter account under a fake name (CatNapped55), and go nuts (“WTF? wheres mittens? wheres my kitty litter tray? OMG. #catnapper #[yourname]”).

Sure, you could contact Twitter, or even sue them; and maybe you could get the account shut down. But what’s stopping your defamer from opening another Twitter account, or moving on to a different website? If someone’s orchestrating a belligerent and ongoing smear campaign against you, there’s no information more vital that the identity of that person. Take away their anonymity, and suddenly they’re vulnerable. To do that, you’re going to need someone who knows what they’re doing – call us, and we may be able to help.

Meta data: Somebody been spreading rumours?